Yes, this a very detailed history. A brief BCC campus overview can be found at Outdoor Afro. Come back/stay if you want a closer look at our unique built heritage!

This article will celebrate and tour many of the buildings of the Bronx Community College campus overlooking the Harlem River in the NW Bronx. Bronx neighbors, artists, architecture enthusiasts, and lovers of all things urban are sure to find something of value here.

The preceding article, entitled ”The Mountaintop: What Bronx Community College Means,” showed us which college president oversaw this school’s ascent to University Heights from scattered buildings along Jerome Avenue. Now, we will explore the more popular buildings of this center of learning.

Contents

General Campus Description

The Marcel Breuer Legacy

List of Breuer-designed Buildings

The Stanford White Legacy

List of White-designed Buildings

More Noteworthy Buildings

Selected Bibliography

General Campus Description

The Bronx Community College (BCC) campus, formerly New York University’s undergraduate schools of engineering and arts, consists of thirty-one buildings. This forty-seven acre National Historic Landmark has evolved under the care of several managers beginning with wealthy nineteenth century home owners. Today’s students know those former homes as South, Butler and MacCracken halls as well as Altschul House beyond campus gates. The period in which the landscape was consolidated into a campus for higher education followed the acquisition of William T. Mali’s estate by New York University in 1892. BCC acquired all of the buildings within the gates of the former NYU University Heights campus much later. Interestingly, most Heights campus buildings outside the college fence were not purchased by New York State for the use of the community college and are operated today as privately owned housing or have been replaced by new structures and land uses. Such was the fate of a number of fraternity houses now enjoyed by neighbors as private homes. BCC held its first classes here on Saturday, September 8, 1973.

The earliest period of existing buildings includes three mansions from a time when the commuter railroad we now call Metro-North was a primary means of transport into Manhattan and suburban life became an option for the well off as well as the tradespeople who served them. The campus was designed and planned with the Greco-Roman tastes of the founding architect Stanford White (1853-1906) of the nationally renowned firm McKim, Mead and White. Much later, a contrasting although somewhat deferential master plan with very different structures came from the architectural studios of Marcel Breuer (1902-1981) who started his career as a painter, sculptor and architect in pre-war Germany at the Bauhaus school along with many distinguished modern designers. Much comment has been made over the years about the differences of style between these two dominant designers. Breuer reflects on this in a 1957 letter reproduced in the book Marcel Breuer, Architect:

“The problem of harmonizing a new building with another architectural style surrounding it comes up again and again. I had to face this situation not only with Hunter College, but in my Embassy Building at The Hague, Holland, and the UNESCO Building in Paris. As a matter of fact, thoughts in this direction were somewhat more justified in the latter two cases, because the surroundings are truly historical and not, to begin with, an imitation style. My own point of view is that no such thing as “harmonizing” exists, and that everything harmonizes if it is on a certain level. The best example of this is the Piazza San Marco in Venice. It would be difficult to imagine more clashingly varying styles than are represented there, three of them next to each other, and resulting in the most photographed and visited place in the world. There are certain means of architecture which can be used as connecting bridges between “styles” and “periods.” For instance, the material used for the facing of a building, or the general feeling of scale (larger or smaller scale as the case may be) though even these means of architectural expression should not be used to “harmonize” without realizing the inherent danger of falsification of ideas” (Hyman 144-145).

We see Breuer attempting to bridge his modern style with the traditions he found. He adopted Stanford White’s color scheme of tan Roman brick and used unpainted concrete to substitute for carved limestone. His rubble stone retaining walls bear precedent in the rocky foundations of the converted country homes of Schwab (South Hall), Mali (Butler Hall) and Andrews (MacCracken Hall).

The Marcel Breuer Legacy

Marcel Breuer (1902-1981) was a German-trained architect from Hungary who became a widely respected teacher and working architect with many international commissions as near-by as the Whitney Museum of American Art (Manhattan) and less close projects like the Paris headquarters of the United Nations Scientific, Economic and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). He was also a furniture designer and lived comfortably during the global depression of the 1930s from royalties on a metal tube cantilever chair he designed. He and his firm left other marks on the Bronx at Lehman College where an associated architect from his firm is responsible for Shuster Hall and the former library now acting as art class and gallery space dating to 1960. Brutalism is his dominant style characterized by raw expression of forms, functions and especially materials. His rubble stone walls erected along clean lines were a life-long trademark and are forceful at BCC. His first Bronx projects were among his earliest in all of New York City. Most dates of construction given in this blog are from the book Marcel Breuer, Architect. Cornerstones at Colston and Polowczyk may read differently.

List of Breuer-designed Buildings

[Morris] Meister Hall/ Originally Technology II

Date: 1967-70

Further reading: Marcel Breuer, Architect and Marcel Breuer, A Memoir

Morris Meister was the first President of Bronx Community College and a former Principal of the Bronx High School of Science.

Distinction: Last Breuer building to be built at University Heights campus. This building was designed for use as engineering and science laboratories and classrooms among other functions. It may be the most independent statement, in scale and aesthetics, by Breuer, on campus owing the least in inspiration to the original Stanford White designs it shares the quadrangle with. Extensive use of undressed cinder blocks and concrete make this a purely Brutalist design. The intimate Schwendler Auditorium in the basement provides a clear style contrast point when compared with the neo-classical Gould Memorial Library Auditorium (restored around 1999 by BCC). This building provides an important opportunity to compare and contrast Breuer’s later work at BCC with other commissions internationally because it contains his trademark deeply sculptured walls in precast concrete. Robert Gatje, once an associated architect in the Breuer firm writes in Marcel Breuer, a memoir “…these signature ‘folded’ concrete walls were first created for an IBM property on the French Mediterranean in 1960 and later employed for a similar design at SUNY Buffalo’s Chemical Engineering Building. In these and other buildings, creative vibrancy is expressed by the progressive differences of a familiar approach to sheathing a building while accommodating and subtly revealing the functions within.” See Frank’s comment below this article for a discussion of this building’s relation to the NYU campus’ radio station.

[Frank and Lillian] Begrisch Hall

Date: 1959-61

Note: Begrisch lecture hall has a precedent in Konstantin Melnikov’s Workers’ Club, Moscow (1927-28) which Breuer knew of (Hyman 199). Breuer enjoyed the play of light on textured (Begrisch) and molded (Meister) concrete. In her Breuer book, Isabelle Hyman reproduces his sentiments: “The greatest esthetic design potential in concrete…is found through interrupting the plane (surface) in such a way that sunlight and shadow will enhance its form, while through changing exposure a building will appear differently at various moments of the day” (p.155). Although this building has won awards it has also been a source of criticism for detractors of modernism. It retains its original name attributed to NYU donors.

Further reading: Marcel Breuer, Architect

Distinction: This reinforced concrete hulk was the first fully air-conditioned building on campus. Its two lecture halls are supported above a semi-open covered plaza by two cantilevered trusses on the east and west elevations. It was the first in the United States to employ a technology that allowed professors to face their students and have words, drawings, normal and microscopic slides projected by the teacher on a large screen while lights were on and in full clarity. The building was also equipped for television broadcasting. (Source: “New York University Changes the Face of Bronx Campus.” Bronxboro Winter edition. 1963.)

Carl J. Polowczyk Hall/ formerly Gould Hall of Technology

Date: 1959-61

Further reading: Marcel Breuer, Architect. Isabelle Hyman writes on page 199 that this building for science was specifically designed to support the departments of physics, electrical engineering and mathematics.

Note: The main stairwell is impressive in its composition of forms and materials. Modernism is often criticized for being cold; Breuer gives us warm, smooth wooden handrails to guide us from floor to floor. Looking up, you see a distinctive partnership of materials in the construction of the terrazo floors, steel reinforced cast-in-place concrete supports and walls of contrasting plain mosaic tile by other walls composed of cinder blocks. This building shares a view with Butler Hall’s red brick; Breuer adds to this study of brick bonds (patterns) by creating vertically oriented patterns in exterior walls. Less subtle is the soaring canopy on the east façade which reaches out to protect visitors. Compare with his equally assertive but less organic canopy downtown at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

[James A.] Colston Hall/ formerly Julius Silver Residence Hall

Date: 1961

Note: Colston Hall was built as a coed dormitory with different sections separating male from female dorms in a seven-story tower meant to house six-hundred students in double rooms. The adjoining building, nearest the Hall of Fame, was designed to accommodate a student lounge above a kitchen and dining hall. James A. Colston was BCC’s second president, first BCC president at the Heights campus and first African-American president of any college in New York State. According to a NYU data sheet entitled “Residence Halls-Heights” attributed to “Jones,” Julius Silver was a NYU alumnus who graduated in 1922 and partly financed the building which was named for him shortly after its opening.

Further reading: Marcel Breuer, Architect and Marcel Breuer, A Memoir

The Stanford White Legacy

Architect Stanford White (1853-1906) was a native New Yorker whose social life was as much a spectacle as his design career. He was a master of ornament who worked on building interiors as well as total design of structures, even books and ceremonies as with the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus in America. He was a partner in the firm of McKim, Mead and White along with Charles McKim who designed Columbia University in Manhattan around the same time to chunkier, darker-toned effect. Their designs are similar in that they worked in a beaux-arts mode freely referencing and combining Italian and other classical models.

Both campuses’ central libraries command attention on grassy quadrangles intended as campus centerpieces. White designed the University Heights campus as a mature architect and drew a master plan of nineteen buildings of which five were constructed.

It’s important to remember that White’s firm was associated with a new vision in American town planning called the City Beautiful movement impressed on the American public at the Columbia Exposition of 1893 in Chicago, Illinois. The original campus was master-planned even with the purchase and careful control of development on its perimeters and with respect to access to public transportation and local open space (ie. Aqueduct Walk, University Woods Park on Sedgwick Avenue—that street being a main access to the college in the earliest days— and a long gone Harlem River boat house for water sports). At that time, the Bronx was newly part of New York City. New Yorkers knew the area—quickly becoming ‘University Heights’— as the “North Side,” “Annexed District,” “Fordham Heights” or “the 24th Ward.” This land between the Harlem and Bronx rivers was added to New York County on January, 1, 1874. Before that, the land that became University Heights was in the Town of West Farms in Westchester County. Read The Bronx by Evelyn Gonzalez to understand the phased annexation of the Bronx by New York from Westchester County.

CUNY professor emeritus William Gerdts illustrates the tenor of the neighborhood in Stanford White’s time by quoting his age peer writer Jesse Lynch Williams in Impressionist New York: “There is a different feeling in the air up along this best-known end of the city’s water-front. The small, unimportant looking river, long distance views, wooded hills, green terraces, and even the great solid masonry of [the] High Bridge…somehow help to make you feel the spirit of freedom and outdoors and relaxation. This is the tired city’s playground.” This landscape of well being was the ground in which McKim, Mead and White carved out our educational acropolis under the leadership of NYU Chancellor H. M. MacCracken. The most celebrated element of this original scheme is the Hall of Fame for Great Americans and neighboring group of buildings about which much has been written.” See Further reading.

Most dates of construction for Stanford White-designed buildings were drawn from various New York Times articles where the development of this campus was closely reported.

List of White-designed Buildings

Gould Residence Hall

Date: 1896

Distinction: Early dormitory for a NYC non-sectarian college. Butler Hall was the first NYU Uptown dormitory (1894-1898).

Further reading: “Plans for a residence Hall approved by the Council of the University of the City of New York—Site and Appointments.” New York Times 18 Feb. 1896: p.14. Excerpt: “The hall is designed for 112 [male] students, and contains in its four stories 48 studies, each with an open fireplace; 64 bedrooms, accommodating 112 beadsteads; 8 bathrooms, 128 clothes closets… In the basement, which is largely above ground on the east side, will be a music room, two bicycle rooms, two college periodical rooms, and other attractive appointments.” An NYU archives data sheet entitled “Residence Halls—Heights” attributed to “Jones” states, “In 1963, this was completely remodeled and renovated to accommodate 163 women.”

Hall of Fame for Great Americans (painted here by Danny Hauben)

Website: www.bcc.cuny.edu/halloffame; phone: 718-289-5170/5180.

Dates: Design through completion 1892-1912. Dedicated May 30, 1901.

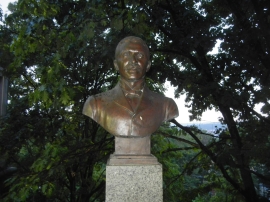

To see the Bronx as a microcosm of America is a theme of the Bronx County Historical Society. The Hall of Fame for Great Americans helps tell that story on multiple levels. This is America’s original Hall of Fame. It includes many sculptural likenesses of popular Americans through the first half of the twentieth century. Less well known, is that the sculptors of those precious images were often highly revered in their own right. While Augustus Saint-Gaudens, a sculptor, is also a Hall of Fame inductee—complete with bust and Tiffany plaque—at least seven of the others are also collected in our nation’s National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.. Their names are: Frederick William MacMonnies, Jean-Antoine Houdon, Walker Kirtland Hancock, Herbert Adams, Jo Davidson, Daniel Chester French, and Edward McCartan. Richmond Barthe (African-American) and a few female sculptors like Malvina Hoffman and Anna Hyatt Huntington are also represented.

Distinction: Below the al fresco colonnade was once a corresponding museum and archives for the Hall of Fame. (source: Your Hall of Fame, NYU Press).

Further reading: “Hall of Fame Dedicated: Tablets of great men unveiled with appropriate ceremony.” New York Times 31 May 1901: p.3. The category Septimi means Seventh Class and refers to miscellaneous professions.

Note: This limestone structure with a granite base has a Guastavino tile ceiling like parts of Grand Central Station in Manhattan. It is believed to be an inverted interpretation of St. Peter’s Square welcoming the faithful to St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, Italy designed by baroque sculptor and painter Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680). Sedgwick Avenue was originally the main approach to the campus which would have made the view of this structure a defining one.

L-R: Language Hall, Gould Memorial Library, Philosophy Hall

L-R: Language Hall, Gould Memorial Library, Philosophy Hall

Language Hall

Date: planned 1892-1894/ opened October 1895

Floor plan: “…gives each professor besides his classroom a room for the department library and advanced work” according to “Ready for Educational Work.” New York Times 7 Sept. 1894: p. 9. By the time BCC acquired this campus, Language Hall was already renovated for executive work space.

Distinction: Believed to have been modeled after the Athenian Temple of Nike.

Source: “New York’s Hall of Fame and What it Stands For.” New York Times 7 Sept. 1913: p.SM11.

Gould Memorial Library

Date: planned 1892-1894/ broke ground 1895/ completed 1899

Distinction: Designed after the Pantheon (translates in English to Temple for all Gods) in Rome. See the inscription on the library’s eastern elevation above the entry doors, “LIBRARIES ARE AS THE SHRINES WHERE ALL THE RELICS OF THE ANCIENT SAINTS FULL OF TRUE VIGOR ARE PRESERVED AND REPOSED.” Like the Pantheon, GML has bronze doors (installed in 1921) and spectacular interior space lit from the dome. This building was a gift of NYU alumnus Helen Gould in honor of her father Jay Gould, railroad speculator, who is buried in grand style at Woodlawn Cemetery, also in the Bronx.

Further reading: “It’s buildings opened: exercises at the University of the City of New York.” New York Times 20 Oct. 1895. Thomas Jefferson, U.S. President and builder, planned the University of Virginia’s campus with a central, domed library and radiating promenade and colonnades leading to complimentary buildings almost a century before Stanford White. Read about and see this precedent in Hugh Howard’s Book, Thomas Jefferson Architect, published in 2003 by Rizzoli International Publications of New York.

[Cornelius Baker] Philosophy Hall

Date: planned 1892-1894/ built 1912-1913

Distinction: modeled on the Temple of Nike in the Acropolis of Athens, Greece.

Note: The harmonious though restrained design acts as a foil to GML. Although many of the buildings built on campus after the death of Stanford White were carefully drafted after White’s neo-classical hand, this is the only one taken directly from his designs; it was financed by the widow of a generous NYU benefactor in honor of her father. Other attempts to complete White’s vision are exemplified by the placement though not design of Loew Hall. White envisioned a residential cluster off University Avenue to accompany Gould Residence Hall.

Ohio Field, named for The Ohio Society which raised a modest amount of money toward the Heights campus building campaign and to which several NYU professors and NYU Chancellor MacCracken belonged. This is the athletic field behind the Brown Student Center.

Date: 1892-1912 Designed by the firm Olmstead and Vaux (designers of Central and Prospect parks in NYC).

Distinction: formed the large athletic and ceremonial space desired but impossible to create at Washington Square campus in Manhattan.

Further reading: “Its Buildings Opened.” New York Times 20 Oct. 1895: p.3 This article tells the story of the naming of the field as told by NYC Mayor Strong.

Note: In 1953, the Student’s Center replaced bleachers from which sports were cheered further bisecting the open green between Gould Residence Hall and Gould Memorial Library occupied by the grassy quadrangle to the west and Ohio Field to the east. The Ohio Society was a major contributor to the building of General Grant’s Tomb in northern Manhattan.

[William F.] Havemeyer Lab

Date: planned 1892-1894/ opened 1895

Distinction: Devoted originally to Chemistry, each floor was designed for a “different division of chemical work,” according to “Ready for Educational Work.” New York Times 7 Sept. 1894: p.

Later designated for the Biology Dept.

Additional Source: “New York’s Hall of Fame and What it Stands For.” New York Times 7 Sept. 1913: p. SM11

Note: According to the unpublished paper A Historical Tour of the Heights by Steven L. Carson, Havemeyer was once surrounded by trees planted by internationally famous persons. This included physicist Albert Einstein whose name and countenance were carved into Hall of Fame Gate by Brinsley Tyrell, installed 1996 across from Ohio field at PS/MS 15 (2195 Andrews Avenue).

More Noteworthy Buildings

[Marcus] Loew Hall/ originally Loew Residence Hall

Date: 1955

Architects: Eggers and Higgins. They also designed the Roscoe C. Brown Student Center.

Style: This mid-20th century institutional modernist building is supported by a steel superstructure and concrete. The brick exterior with ceramic accents serves as environmental protection for the interior and does not support the building. The color was chosen to harmonize with the campus.

Note: According to various New York University press releases of the period, this facility was designed to house 225 students and 4 proctors to watch over them. The sunken rooms off the north and south foyers were originally lounges. There were also rooms for study. Two communal toilets and showers were shared by each floor. Safety and health services offices have been located here since opening day. NYU alumnus Arthur M. Loew (class of 1918), financed one-third of this building’s construction costs as a memorial to his father Marcus Loew, President of Metro-Goldwyn Mayer. The name Loew continues to be associated with the motion picture industry. Source: various NYU Archives documents. See Frank’s comment below this article for a discussion of this building’s relation to the NYU campus’ radio station.

Alumni Gymnasium/ originally New Gymnasium

Date: Phase I, 1931; Phase II, 1950

Style: Free Romanesque

Phase I Architects: Gavin Hadden, Engineer and Architect; McKim, Mead and White, Consulting Architects: Fiske Kimball, NYU Architect

Phase II Architects: Rose and Rose; McKim, Mead and White, Consulting Architects; Fiske Kimball, NYU Architect.

Note: The original gym was described as “constructed in part out of the substantial barn already upon the grounds. It is of wood, on stone piers, with a slate roof, and measures 100 feet long by 65 feet wide. The gallery contains a track upon which twenty laps make a mile…” from “Ready for Educational Work: four new buildings for the City University under roof.” New York Times. 7 Sept. 1894: p. 9. The article continues that four lawn tennis courts had replaced a former garden. According to various NYU Archives documents, especially a press release dated 27 May 1950 entitled New York University to Dedicate New Gym, the current gym had to be built in stages because construction costs continued to rise in the 1930s and through World War II. The building’s first phase included two basketball courts, showers, lockers, and student assembly rooms on three floors and had no decorative facing. The building was expanded and reopened in 1950 with the decorative face in romanesque style we see today. Now deeper in the back and at least one story taller, it featured a “basketball court of maximum size, a swimming pool with six racing lanes…an exercise room, a wrestling room, two team rooms, a locker room, and offices for the coaching and administrative staffs.” The new building provided for “ticket sales rooms and checking facilities for spectators…and folding bleachers to accommodate approximately 1,100 spectators” (NYU Archives).

[William H.] Nichols Hall (formerly University Heights High School/ originally Nichols Building for Chemistry)

Date: Construction began in April 1926

Architect: Augustus M. Allen; Victor Krauss, Engineer

Style: Renaissance revival

Note: Beyond the elegant travertine vestibule is a richly ornamented foyer. It contains brass sconces for lighting, marble walls, ornate terrazzo floors, sturdy solid wood doors with brass handles and neo-classical mouldings in the ceiling originally painted all white, now highlighted with gold. Nichols was a major figure in chemistry and chairman of the board of the Allied Chemical and Dye Corporation and a member of NYU’ Council. He graduated from NYU in 1870 and donated this building in his final years. According to an unattributed folio entitled A Temple of Well Being in the collections of the NYU Archives, the building had a chemistry library on the fourth floor, at least twenty-five laboratories for two-to-six persons and a number of large labs for chemical engineering, organic and inorganic chemistry. Today’s first floor lunchroom is partitioned from what was originally a ballroom.

Guggenheim Hall/ originally Daniel Guggenheim School of Aeronautics

Date: 1925-6

Style: Renaissance revival

Architect: Unknown.

This is a good place to compare and contrast different brick facings within the engineering quad. See different attempts to mimic Stanford White’s original composition of straw, gold and tan roman bricks in New, Bliss, Guggenheim and Sage halls, even Meister Hall. This building is now used for automotive programs and music. The 1963 winter edition of the defunct magazine Bronxboro, in a profile entitled New York University Changes Face of Bronx Campus, wrote “The Aeronautical Engineering Laboratory is being remodelled and a new supersonic wind tunnel capable of simulating speeds of more than four times the speed of sound has been installed.” The article continues, “In addition to academic work, the faculty and staff at University Heights are active in scientific research and annually bring to the Bronx campus more than $14 million in research grants and contracts. Research ranges all the way from liberal arts to the space age engineering and scientific fields.” There was a separate campus building for musical instruction prior to 1973.

Bliss Hall (continuous Home to BCC’s Art Department since 1973)

Date: 1936

Style: Renaissance revival

Architects: Unknown; designed for civil engineering & meteorological instruction.

This building once housed a weather station and several labs. The ceilings of the first floor are notably high. Post-design blueprints in the NYU Archives show a “Conc. Lab” where the Hall of Fame Gallery is today. The room occupied by Project H.I.R.E. is labeled “Mechanical Lab.” The first floor contained a “Mat. Test Lab” occupying much of the southern portion of the first floor with a modest “Photo Room” by the rest rooms. The other floors were designed with three drafting rooms, seventeen offices, and four classrooms.

Sage Hall/ originally Sage Engineering Building

Date: 1918-21

Style: Renaissance revival

Architects: Crow, Lewis and Wick (See Hall of Fame for Great Americans).

Note: This building was built at the southwestern edge of an “Engineering Quadrangle.” The University Heights campus once included science department buildings elsewhere however Bliss and Guggenheim halls are surviving buildings from that cluster within the School of Engineering Science of NYU at the Heights.

South Hall/ originally Gustav H. Schwab House (German)

Date: 1857

Style: Asymmetrical villa by a builder named Truby (Twomey).

Note: South Hall was not acquired as part of the academic campus until 1908 when it was purchased by NYU from the Schwab family according to NYU, 1832-1932, edited by Theodore Francis Jones. It is captioned in 1930s-1940s NYU booklets as “South Hall Dormitory: College Infirmary.” In later NYU Archives documents through 1971, it is designated “School of Engineering and Science Administration.”

Further reading: White, Lucy Schwab. Fort Number Eight: The Home of Gustav and Eliza Schwab., 1925. This book references life at the Schwab house and a cemetery for the enslaved from the former Archer Estate (owned earlier still by Adrian Van der Donck) once west of today’s Sedgwick Avenue. According to Bill Twomey’s Do You Remember column in the Bronx Press Reporter of November 2, 2006, The Schwab estate began as eight acres purchased at one thousand dollars per acre. In 1869, eight additional acres were purchased at $2500 per acre. It was common in the nineteenth century for elite houses to be named. The moniker Fort Number Eight was adopted from the British fort that occupied the site during the American Revolutionary War. Permanent memorials to that war camp are parallel to South Hall at the summit of grassy Battery Hill.

[Charles] Butler Hall, after the President of the Council of NYU during the Uptown founding period/ originally William T. Mali House (Belgian)

Date: 1857

Style: (compact red brick) by a builder named Truby (Twomey, Bill. Do You Remember—The Little Boulder at Fort No. 8. Bronx Press Reporter. November 2, 2006)

Note: Renovated by 1894 as a dormitory for 40 students with bathrooms in the basement and steam heat in every room according to “Ready for Educational Work: four new buildings for the City University under roof.” New York Times. 7 Sept. 1894: p. 9. According to NYU Archives files, it was converted to offices and classrooms, especially for the study of Biology after 1898 when Gould Residence Hall and local fraternities had come to satisfy dormitory needs.

Roscoe C. Brown Student Center/ originally [Frank J.] Gould Student Center (Roscoe Brown was a BCC president; Gould was a donor).

Date: 1953

Style: Mid-century institutional modern

Note: Designed by Eggers and Higgins, contains a mini performance space and cafeteria as well as student government offices and a book shop. A day care center occupies the south wing. Originally headquarters to a daily student newspaper. BCC’s first headquarters of the Communicator, a student newspaper later relocated to Meister Hall and other locations since.

[Henry Mitchell] MacCracken Hall/ formerly Loring Andrews House, subsequently the New York Skin and Cancer Hospital as per the Loring will/ originally George B. Butler House

Date: circa 1860

Style: Victorian with post construction renovations.

Note: NYU Chancellor from 1891-1910, MacCracken was a former professor of philosophy. He and his wife moved into this gracious house in spring 1894 according to “New York City University.” New York Times. 30 April 1894: p.9. He bought the house as a private residence although it was used for periodic school business and social events; NYU acquired the site in 1925. Loring Andrews., an Anglo-American, was a leather tanning merchant who endowed NYU professorships to the tune of $100,000. Under NYU ownership this three-story building housed the history, speech and other departments during different periods. WNYU broadcast from MacCracken Hall until Meister Hall (then Technology II) was built. See Frank’s comment below this article for a discussion of this building’s relation to the NYU campus’ radio station.

[Louis and Jeanette] Altschul Hall, a.k.a. BCC Child Development Center, formerly [Richard W.] Lawrence House (name was changed in 1960 by NYU and kept by BCC).

Date: Pre-war (WW II). Multiple interior renovations.

Style: Neo-Tudor

Note: An untitled NYU press release dated 16 November 1960 announces a renovation of the “12-room structure to house the three religious organizations on campus—the YMCA, the Jewish Cultural Center and the Newman Club. Each of the organizations will have independent space for varied activities, and there will also be quarters for joint affairs. Palisades Handbook, published by New York University in 1940-1941 describes Laurence Hall (old name) as “the student activities center for the Heights. Recently renovated with funds appropriated by the Student Council, it contains, in the basement, a cabin room for informal luncheons; on the first floor, the offices of the National Youth Administration branch at the Heights and of the Lawrence Hall staff, and a large drawing room; and on the second and third floors the office of student publications.” The earlier name of Lawrence House derived from the former owner and resident who was a trustee and benefactor of New York University.

Selected Bibliography

Lowe, David Garrard. Stanford White’s New York. New York: Watson-Guptill,

1999

Dolkart, Andrew S. Guide to New York City Landmarks. New York: John Wiley

and Sons, 1998

White, Norval, and Elliot Willensky. AIA Guide to New York City. New York:

Three Rivers, 2000

The WPA Guide to New York City: The Federal Writers Project Guide to 1930s

New York. 1939. New York: New Press, 1992.

Gatje, Robert F. Marcel Breuer: A Memoir. New York: Monaceli Press, 2000.

Hyman, Isabelle. Marcel Breuer, Architect: the Career and the Buildings. New

York: Abrams, 2001.

White, Samuel G., and Elizabeth White. McKim, Mead and White: The

Masterworks. New York: Rizzoli, 2003.

View onto the elite residential life of the pre-campus period via Gustav Schwab:

Ultan, Lloyd and Barbara Unger. Bronx Accent: a literary and pictorial history of the borough. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers UP, 2000 pp.35-37

This document was inspired by the following article:

Gray, Christopher. “Not What Stanford White Envisioned, but Notable.”

New York Times 26 Nov. 2006: RE9

Cancel, Luis R., Timothy Rub, Evelyn Gonzalez, and Richard Plunz.

Building a Borough: Architecture and Planning, 1890-1940: An Exhibition Catalogue Sponsored by the J.M. Kaplan Fund. New York: Bronx Museum of the Arts, 1986.

Perspectives on American Sculpture before 1925: A Symposium Sponsored

by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Ed. Thayer, Tolles 26 Oct. 2001.

New Haven: Yale UP, 2003. Note: Data on the L.T. Scherman bust.

Johnson, Robert Underwood. Your Hall of Fame. New York: New York UP,

1935.

Morello, Theodore, ed. The Hall of Fame for Great Americans at New York

University. New York: New York UP, 1967.

The Hall of Fame for Great Americans (pamphlet). New York: Bronx Community

College.

McEvoy, Dennis. The Hall of Fame for Great Americans (pamphlet). New York:

Bronx Community College, 2003.

Gerdts, William H. Impressionist New York. New York: Abbeville Press, 1994.

See: p. 175 for description of Stanford White-era University Heights and pp.196-197 for descriptions and reproductions of GML in period fine art.

Gonzalez, Evelyn. The Bronx. New York: Columbia UP, 2004.

Twomey, Bill, The Bronx, In Bits and Pieces; iUniverse; Lincoln, Nebraska;

2003; pages 98 and 99

Twomey, Bill, The Bronx Times Reporter; Bronx, New York; October 5, 2006;

page 41

Twomey, Bill, The Bronx Times Reporter; Bronx, New York; November 2,

2006; page 47

Special thanks are offered to the NYU Archives for making available the most complete set of documents on the architecture and design of the University Heights campus and to Bronx Community College’s Library for its on-line subscription to historic and contemporary New York Times articles.

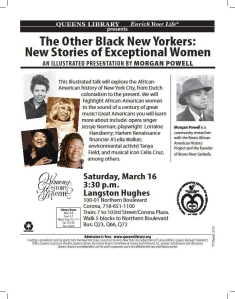

Morgan Powell is a Community Researcher with the Bronx African American History Project. As a landscape designer and sustainable agriculture activist for over a decade, he’s also been a volunteer on numerous environmental efforts throughout NYC, especially power point talks under the name Bronx River Sankofa.

His talks and walking tours have been received by over 1,300 New Yorkers at venues like the New York Public Library, Cornell University and the City University of New York. Morgan writes for the national website Outdoor Afro and other blogs. His on-line videos and other media celebrate the history of African-American New York beyond cliché facts, historical figures and neighborhoods with an eco-twist.